Nunn on the Conservation of Meeson

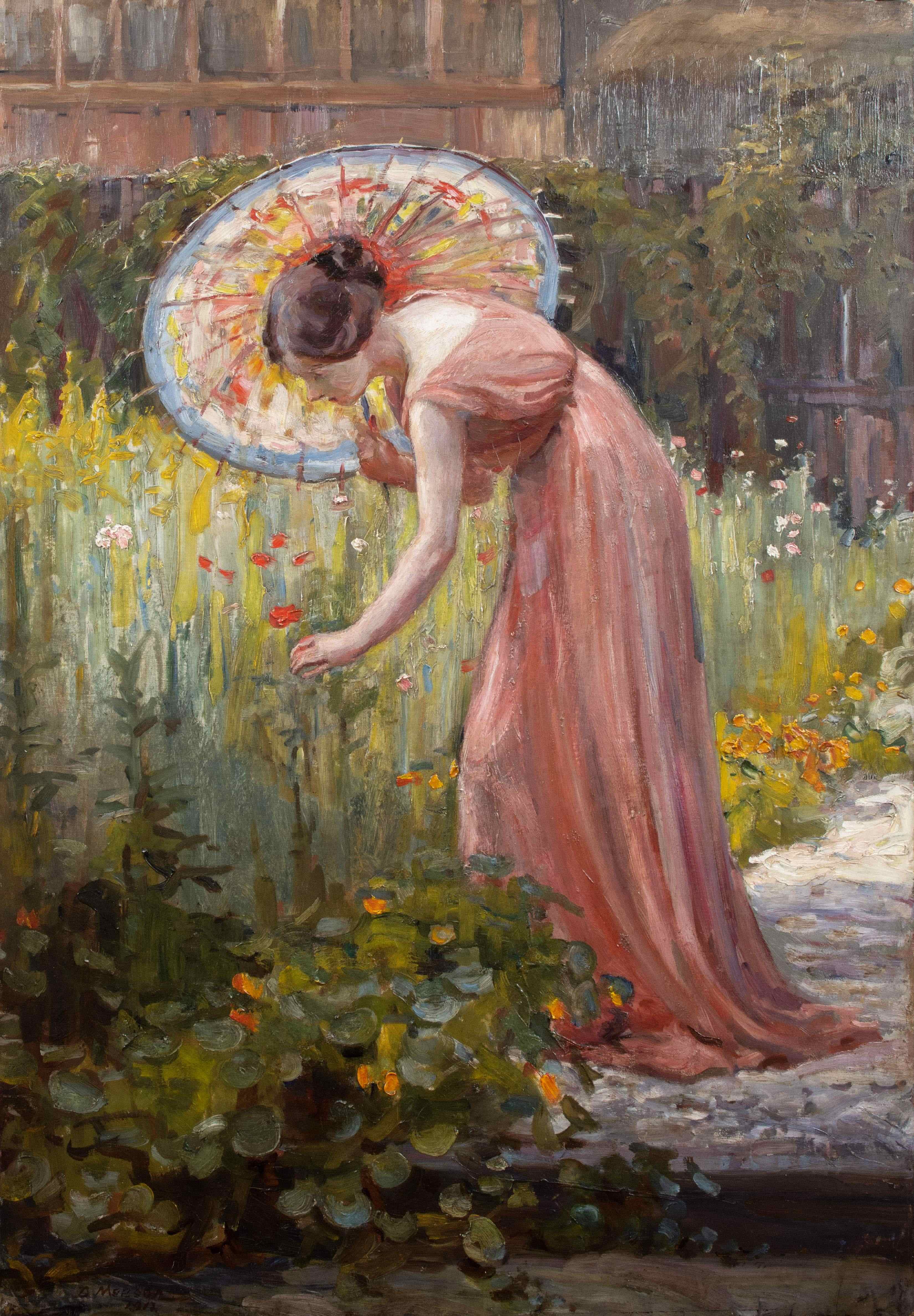

Dora Meeson’s In a Chelsea Garden (1912) has returned to Castlemaine Art Museum following much needed conservation. After a number of cracks were identified in the painting, CAM commenced the Cracking Appeal in 2022 to raise funds for its restoration. A sincere thank you to the individual donors who generously supported the Cracking Appeal and, in doing so, the endurance of the collection.

In this personal Reflection, painting conservator Catherine Nunn demonstrates the revealing nature of conservation interventions – uncovering the artist behind the painting.

Catherine Nunn on the Conservation of Dora Meeson

As a painting conservator, I spend time with lots of different artworks. Paintings generally come to me for a few weeks or months, they share my workspace, observe my daily studio rituals, and submit to my conservation ministrations. When their treatment is complete, they return to their custodians. Usually, I maintain a level of professional distance that keeps me from getting too attached to the artworks. However, when I emailed CAM to report that Dora Meeson’s In a Chelsea Garden was ready to return to Castlemaine after conservation in my studio, I felt really sad.

I’m still puzzling over why I felt this way. Of course, this is a beautiful and serene painting: an elegant lady gracefully leaning to pick a flower in the verdant tranquillity of a Chelsea garden. Maybe it’s just because it’s such a lovely painting that I didn’t want it to leave? Possibly, but I think there’s also something else.

As a conservator, I get to see paintings in ways that aren’t possible when they’re hanging on the wall in a gallery. It’s a privilege of my profession and one of the most exciting parts of being a conservator. When paintings are un-framed for examination and treatment, sometimes unexpected discoveries emerge. These findings deepen our understanding of the artist’s work, and I think that’s why I became so attached to this piece.

For example, when I removed In a Chelsea Garden from the frame for treatment, I could see that the paint layer extends beyond the top edge and wraps around the back of the artwork. This suggests that Meeson originally painted the picture with a longer format; the fence in the background would have extended higher into the picture plane. For some reason, the artist has decided to reduce the height of the painting, perhaps to create a more balanced composition. Noticing these alterations provides insight into an artist’s practice and is a part of the ‘object biography’ of an artwork. It’s a material reminder of the thought and hard work that went into making a painting. That good things go through many iterations before the final product is presented to the world.

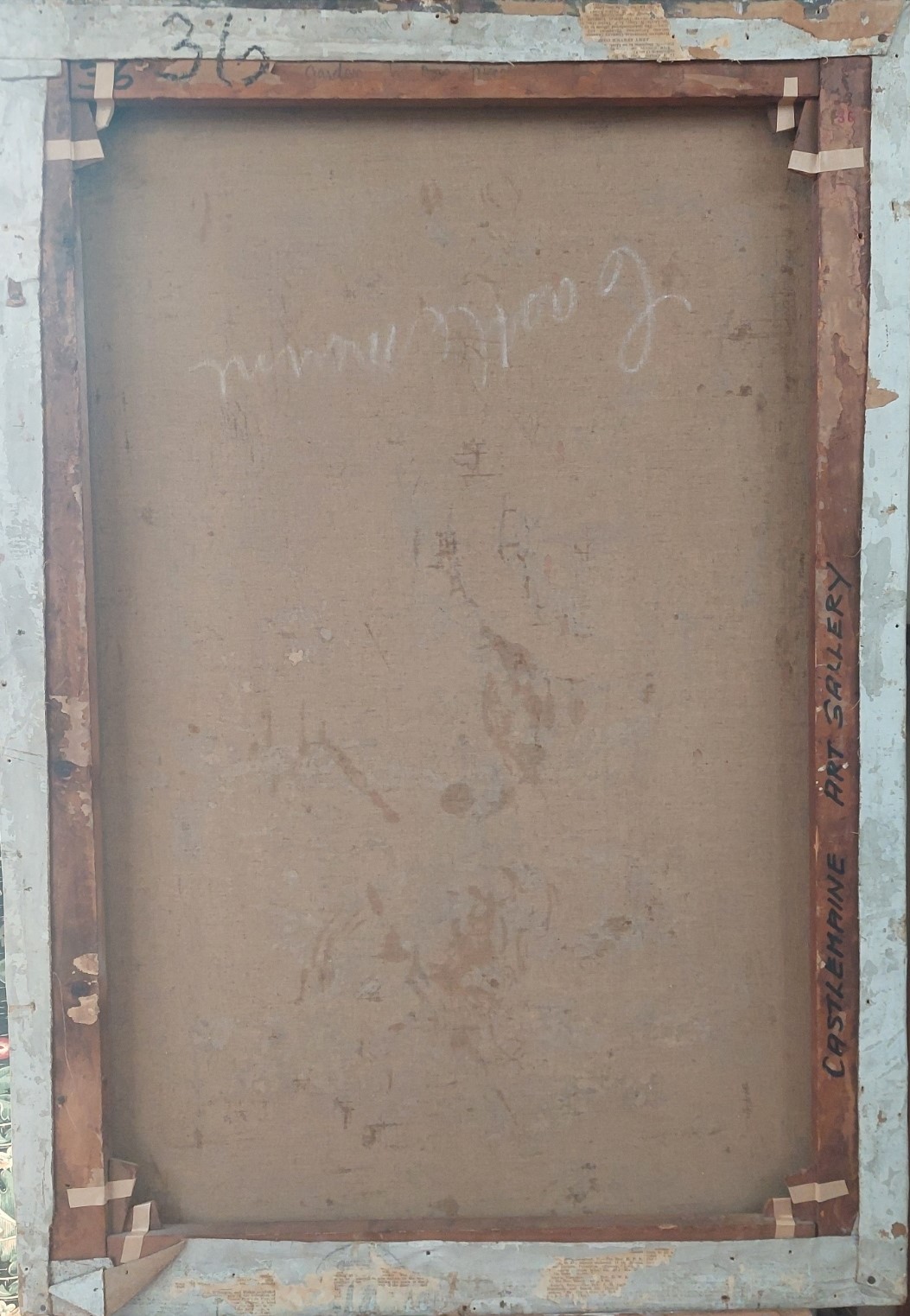

There’s also another hidden detail on the back of this painting. On the wooden stretcher (the wooden structure that supports the canvas), I found a pencil inscription, probably written by the artist. The first few words are partially covered by old brown paper, but I could make out:

“[In a Chelsea] Garden by Dora Meeson (Mrs George J Coates)

… Glebe Place, Chelsea, N3”

Dora Meeson lived with her husband, and fellow artist, George Coates at 52 Glebe Place, Chelsea, London. In the inscription, Meeson identifies herself as Mrs George Coates, typical for a married woman of her era. However, research reveals that, unusually for the period, she became the principal breadwinner of her partnership, painting popular subjects to sell, including studies of children, tourist souvenirs and rural scenes [1].

She and her husband were active in the suffragette movement and through her work she attempted to break down the social barriers that limited women artists to domestic subjects. She is well known for her paintings of the Thames River and the traditionally masculine subject of docks and cargo ships, documenting the industrial and insalubrious environment of working wharves (not considered a suitable place for a Chelsea lady). While the inscription on the back of In a Chelsea Garden identifies her as ‘Mrs George Coates’, her career reflects an independent and emancipated woman.

The conservation of In a Chelsea Garden involved carefully cleaning the paint surface to remove accumulated dirt and grime. The paint is thick and juicy, with many peaks of impasto that create little ledges that are perfect for catching dust!

One area of paint was cracked into sharp shards that were vulnerable to being snapped-off. I used a solvent-vapour softening technique to gradually relax this thick, brittle paint. Finally, I ‘inpainted’ some small paint losses and returned the painting to the frame. In a Chelsea Garden is now clean and conserved, ready to be enjoyed by CAM visitors once again, but (sadly for me) no longer in my studio.

Notes

1 Scott, Myra, https://www.daao.org.au/bio/dora-meeson-coates/biography/ [accessed 5 June 2023].