Bunbury on Thake

Writer and curator Alisa Bunbury was an Honorary Fellow at the State Library of Victoria in 2018, where she researched their rich holdings of Eric Thake material, including paintings, gouaches, prints, bookplates, photographs and design projects. Here she turns her attention to a delightful watercolour in the CAM collection, one that seems prescient in this time of social isolation. This follows an earlier Reflection on Eric Thake by Christine Bell.

Bunbury on Thake

Many of us are feeling housebound in 2020—inside our homes, looking out at the world. As I write this, we Melburnians are forbidden to leave our homes after dark. Castlemaine Art Museum’s moody gouache The Night Moth (1951) may be evocative for many viewers this year.

One of Melbourne’s most important modernist artists, Eric Thake took great enjoyment in depicting windows, reflections, shadows and silhouettes, which enabled him to play with our perceptions, creating a clever confusion. He was among the earliest artists in Australia to explore Surrealism, and a gentle, often humorous, ambiguity pervades his art. In this mysterious image it takes a moment to realise what we are looking at, or indeed what Thake is looking at: his dark shadow on the window pane enables us to see through to the grass and spindly tree trunks, while simultaneously we see, reflected but reversed, the room behind him, the map on the wall in mirror-image (the boot of Italy is visible at the bottom). As Thake looks out, the moth outside is trying to get to the light source within, which we can’t see but which is essential to this image.

Thake’s early training was in the art department of a Melbourne process engraving firm, while he studied after hours first (briefly) at the National Gallery School, and then with the modernist teacher George Bell, who encouraged him to simplify and strategically compose his images. Thake also gained inspiration from postcards and magazines of contemporary European art in Gino Nibbi’s Leonardo Art Shop.

From the late 1920s Thake was exhibiting and receiving recognition for his paintings, prints and bookplates. Thake’s art came to public scrutiny when his Surrealist painting Salvations from the Evils of Earthly Existence (1940) was reluctantly accepted into the National Gallery of Victoria’s collection, after vehement opposition from the conservative director J.S. MacDonald and uncomprehending trustees.

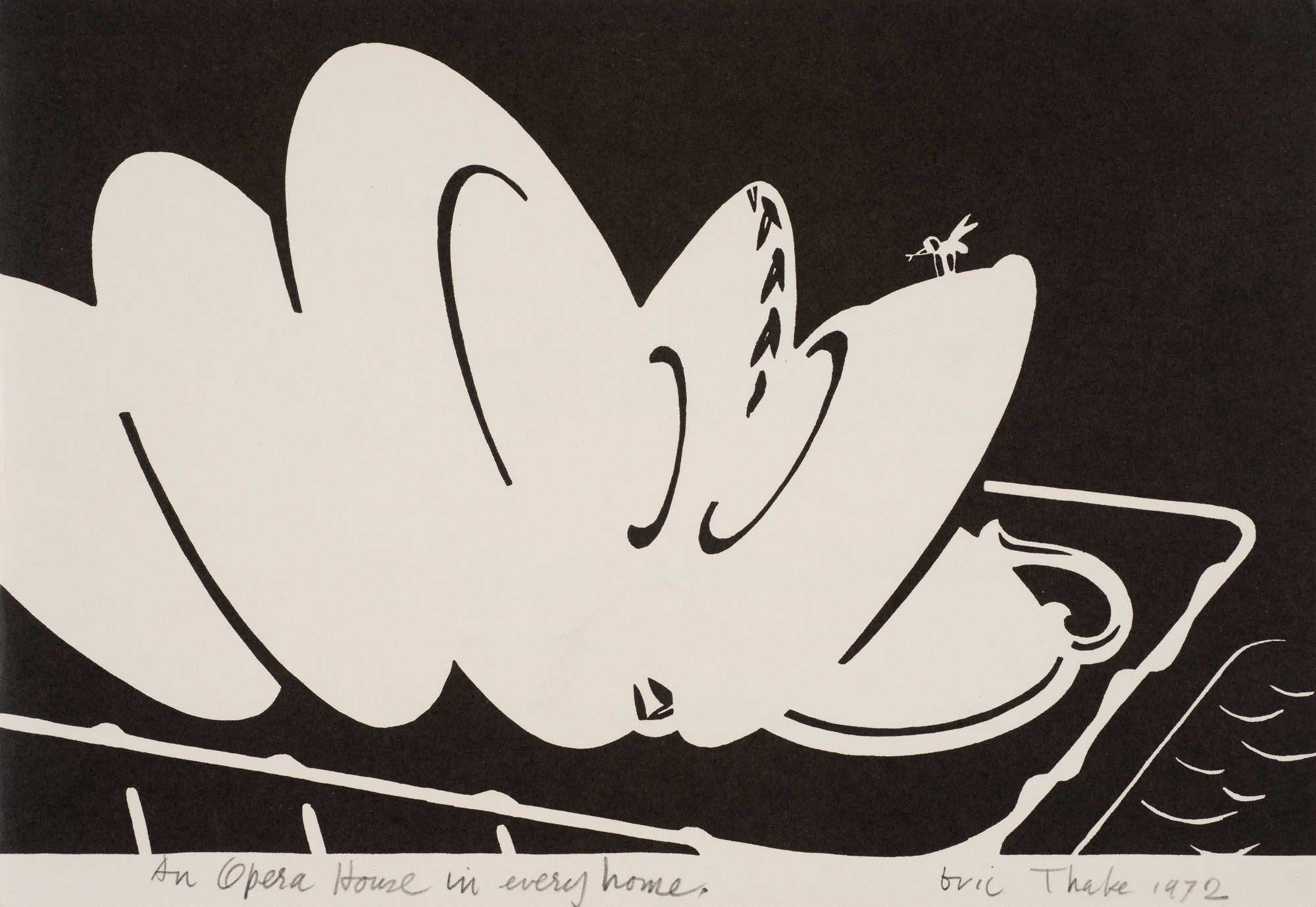

Thake is renowned for finding inspiration in the world around him, as with his best-known linocut, his Christmas card for 1972, An Opera House in Every Home, which captures the repeated curves of dishes drying beside a sink. His only overseas travel was two trips through northern Australia to South East Asia while serving as an official war artist for the RAAF (1944–45). Otherwise, his travel was within Australia, his love of walking and his inability to drive allowing him to continually observe his surroundings.

He was an inveterate sketcher and always carried a sketchbook with him. The Night Moth is based on sketches that Thake made during a family holiday at Metung, in Gippsland, so while he presents himself as a lone figure in this scene, in fact the old house was bustling with two families and numerous children gathered for Christmas. (1) There’s someone at the front door (1951, NGA) was also inspired by this holiday, showing a giant stuffed fish propped up beside the door. The Night Moth was purchased by the Castlemaine Art Museum from Thake in 1958 and was included in his major retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1970, as well as in exhibitions at the Geelong Art Gallery in 1976 and Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum survey of their rich holdings of his art in 2006.

Alisa Bunbury

September 2020

(1) There’s someone at the front door (1950, NGA) was also inspired by this holiday, showing a giant stuffed fish propped up beside the door. My thanks to Jeni Beaty, Thake’s daughter, for her recollections (22 August 2020).